Brave New Worlds: Images as Portals, Prototypes, and Futures

Images as Portals, Prototypes, and Futures—an exploration of how artists are using AI tools, generative workflows, and digital world-building to create new mythologies, reimagine archives, and prototype speculative futures.

Fuser

December 3, 2025

Brave New Worlds brings together a group of artists whose practices range from post-photography, to portraiture, to digitally mediated myth. Each engages with the visual field as a site of exploration, where new cosmologies are not just imagined, but built. What binds these artists’ work is not in their aesthetics, but in their shared commitment to world-building as a critical and continuous gesture—a way of articulating alternate realities and futures that extend beyond the constraints of the present.

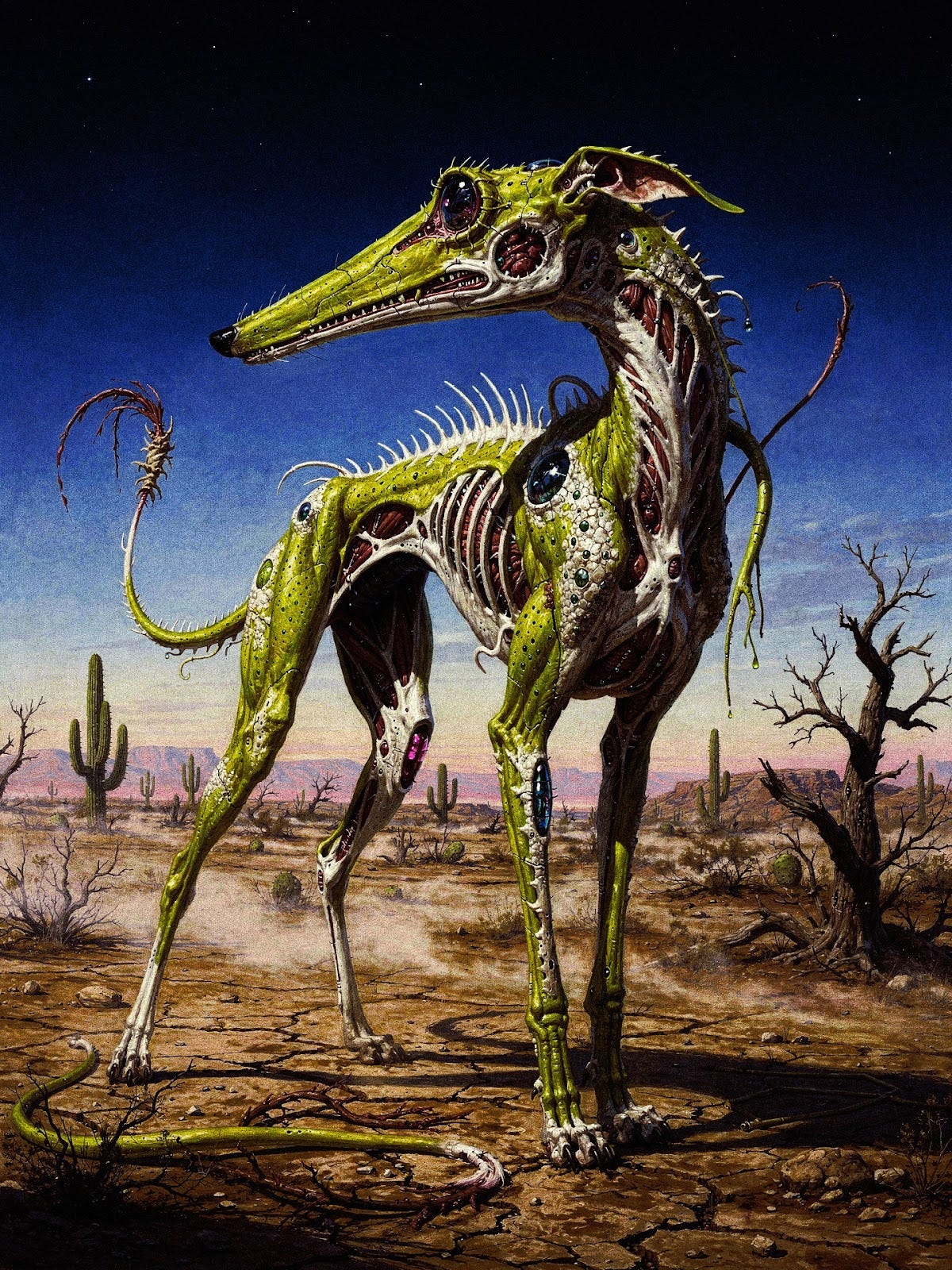

Ikaro Cavalcante (occulted), a Brazilian non-binary artist, explores identity and embodiment through luminous, hybrid figures that occupy a threshold between organic and machinic life. Across their images and tattoo work, the human body becomes porous and reconfigurable. Zak Krevitt’s work extends this inquiry through portraiture and abstract figurative painting, shaped in collaboration with machine learning models—generating creatures that feel both familiar and uncanny.

Serwah Attafuah’s atmospheric dreamscapes push into mythic futurism, staging Black cyber-deities within radiant, impossible architectures. Her worlds are portals: vibrant supra-realities that break the bounds of dominant cultural narratives. And taking a more minimalist approach, hypereikon uses abstraction and procedural logic to probe the metaphysics of the image itself. Their visual experiments test the boundaries between symbol, surface, and signal. These artists have all taken different approaches to working with Fuser, each proposing that brave new worlds are already here, flickering into view: fragile, radiant, plausible.

How does your practice engage with speculative world-building or alternate futures?

Serwah Attafuah: I create surreal cyber dreamscapes and heavenly wastelands populated by Afro futuristic abstractions of self. They are my digital sanctuaries where ancestral traditions morph into sovereign futures. These speculative worlds refuse limitations in physical space, offering refuge where past and possibility converge.

Zak Krevitt: My practice has often focused on people that took the process of human representation into their own hands. Bio-hackers, furries, club kids, queer creatives, drag queens—I’ve always had a fascination with, and deep respect for, people that emancipated themselves from the constraints of what society says you’re supposed to look and act like. People that have the audacity and authenticity to live in a tailor-made world of their own making. Once these photographs enter my archive, I play with their juxtaposition to build out my own versions of the world, each person a word or sentence in a paragraph I’m constantly rearranging.

Ikaro Cavalcante: Because my work is always rooted in memory and identity, I constantly think about new possibilities of existence, whether through matter or the virtual. I don’t approach these worlds as escapism, but as projections of my inner lived experience, where the subconscious becomes architecture. Each piece becomes a portal to a timeline in which emotion and reason blur into each other, coexisting rather than opposing.

Hypereikon: Our practice engages with speculative world-building by starting from the ecological realities that surround us rather than from distant sci‑fi futures. We look at wetlands, rainforests and river systems around our cities, and imagine them as post‑natural ecologies where plastic, data and organic matter share agency. Through generative audiovisual environments, we build worlds in which digital infrastructures and living systems are already entangled, proposing alternate futures that feel like an intensified version of the present rather than an escape from it.

2. What role does AI play in your current creative process?

Serwah Attafuah: AI has played many roles in my practice over the years—I nearly demolished my dodgy first laptop a decade ago trying to get early GANs working. Currently I’m exploring vibe coding with CSound and integrating that into my music practice.

Zak Krevitt: As a documentary photographer I was always dedicated, almost religiously, to the present moment: capturing the material world, as honestly as I could as it existed in front of me. I love the process and history of documentary, but I felt limited by the constraints of that medium and the material world. With AI, l like to engage in surrealist daydreaming, dadaist wandering, based on frayed and tangled threads of imagination, starting within me, but quickly moving outside of myself.

Ikaro Cavalcante: AI for me isn’t a tool of replacement, but a catalyst for distortion, a way to deconstruct the body and rebuild it through intuition rather than anatomy. It allows me to merge photography, 3D, texture and sculpture into a single living organism, something that grows beyond what I could traditionally control. Through AI, I find new choreographies for my own subjectivity.

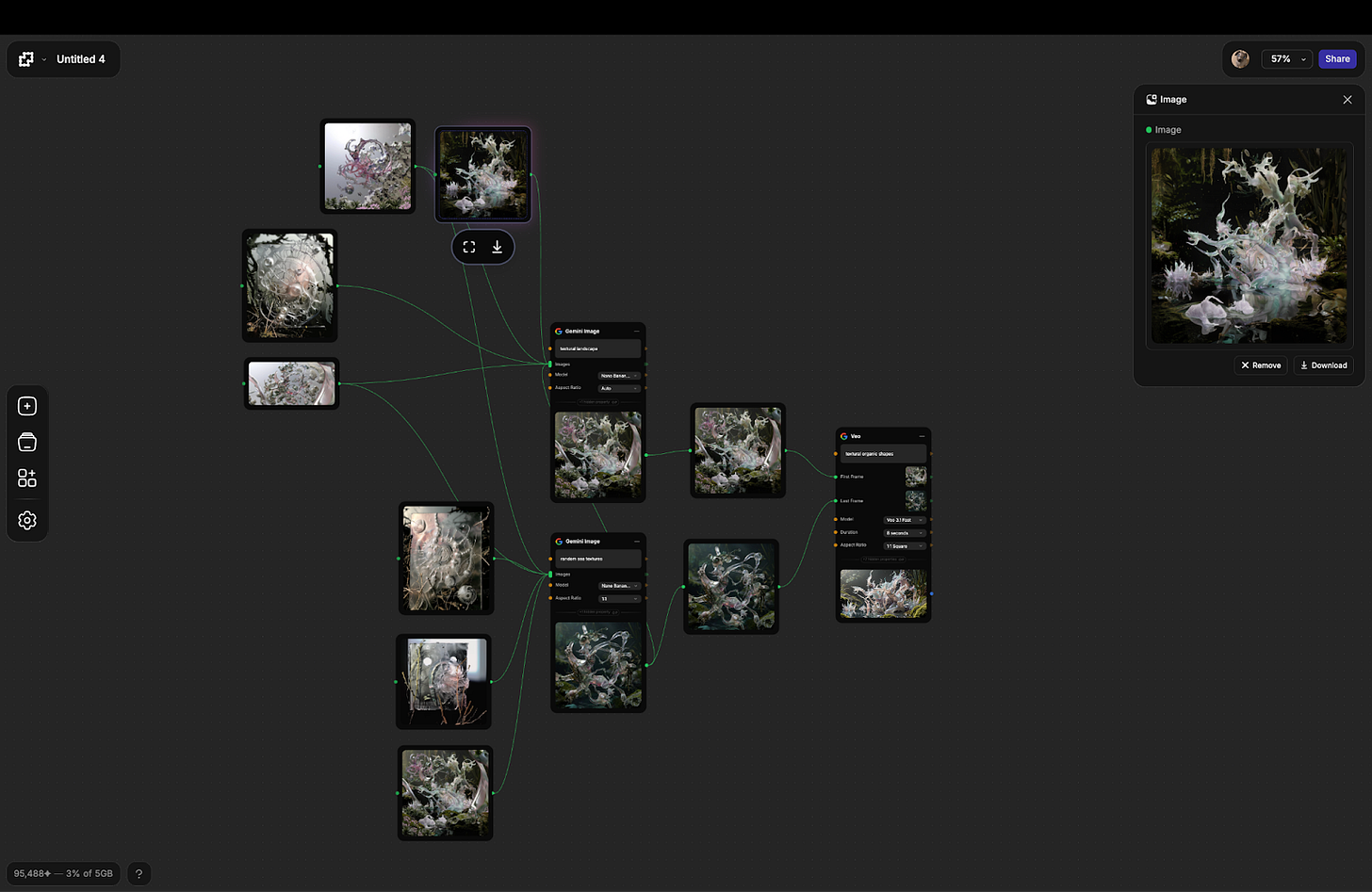

Hypereikon: AI functions in our practice as a kind of prosthetic imagination rather than a neutral tool or an imitation of human intelligence. We sketch initial seeds—texts, sound fragments, images—and then let emergent outputs from AI models redirect the process, creating feedback loops where we continually remix, curate and reconfigure what appears. Working across modalities (text ↔ image ↔ video ↔ sound), we use AI to navigate latent spaces of our shared digital archives, surfacing unexpected associations and speculative ecologies that would be hard to design in a purely linear way.

3. What did Fuser enable here that felt new or surprising to you?

Serwah Attafuah: Image to 3D mesh is something that felt super new to me. Fuser enabled me to liberate an Asante ceremonial helmet: it was most likely looted from Kumasi and it’s now held in the British Museum’s archive. It was pretty heartwarming transforming it from a cold flat photograph into a 3D asset with the help of Fuser. It felt like an act of return; to bring sacred objects home on my own terms.

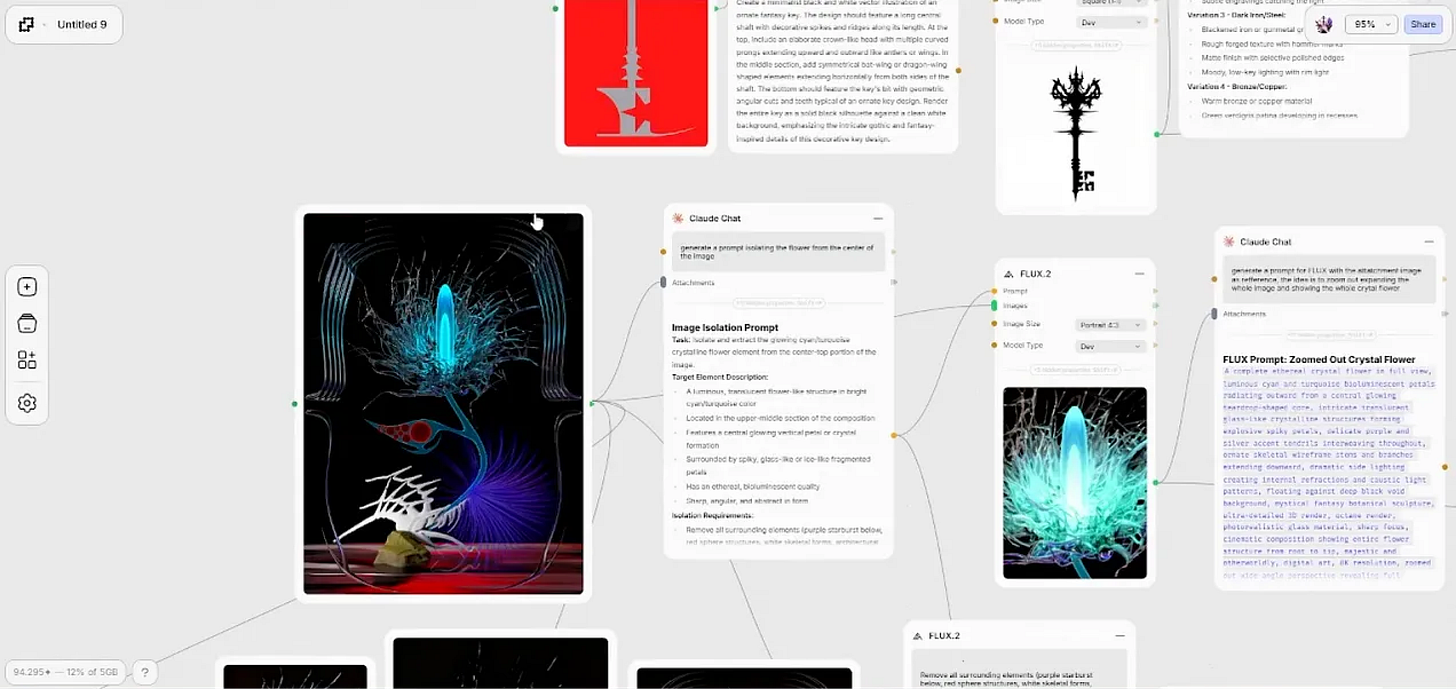

Zak Krevitt: My workflow in fuser leveraged two main functions that made for a really interesting and additive experience, analysis and iteration. First, I brought in some of my previous work, and used a Claude Chat node to analyze the images, summarize their aesthetics, and then combine that with a novel prompt I wrote out. Then, I used the output of that node as the prompt input or a Flux.2 Image Node. The image output of that node was then piped into a second Flux.2 node as the base image, with a second Claud Chat prompt expansion as the prompt input for that second Flux node. I daisy chained several of these together, so that I could explore multiple variations of the same image, letting them pick up image data from each step along the way. This felt like experimental screen printing, changing the screen slightly each time I added a new color to create intricate details in the mismatched screens. This let me get some really interesting details and aesthetics that I couldn’t have achieved from a single prompt and image output.

Ikaro Cavalcante: Fuser allowed me to experience a node-based workflow for the first time, which opened space to explore visual styles far beyond my usual practice. It became a bridge between my 2D and graphic-design references and the older 3D and photographic phases of my work, without forcing them into the same language. What surprised me most was how these different aesthetics could coexist fluidly, as if they had always belonged to the same world.

Hypereikon: Fuser made it possible to think at the level of the whole creative system instead of juggling a tangle of separate tools and interfaces. Being able to orchestrate different models and modalities from one place removed a lot of low‑level friction and let us stay inside the conceptual and visual flow of the project. What felt most surprising was how quickly we could move from a rough idea to a coherent, evolving visual universe—iterating almost performatively, as if we were live‑coding with AI rather than managing a pipeline.