The Graph Will Set You Free: Why Every Creative Tool Is Becoming a Node Canvas

When AI turned the creative process into a network problem, graphs came to our rescue. After 60 years of false starts, visual programming has found its moment.

Hirad Sab

November 6, 2025

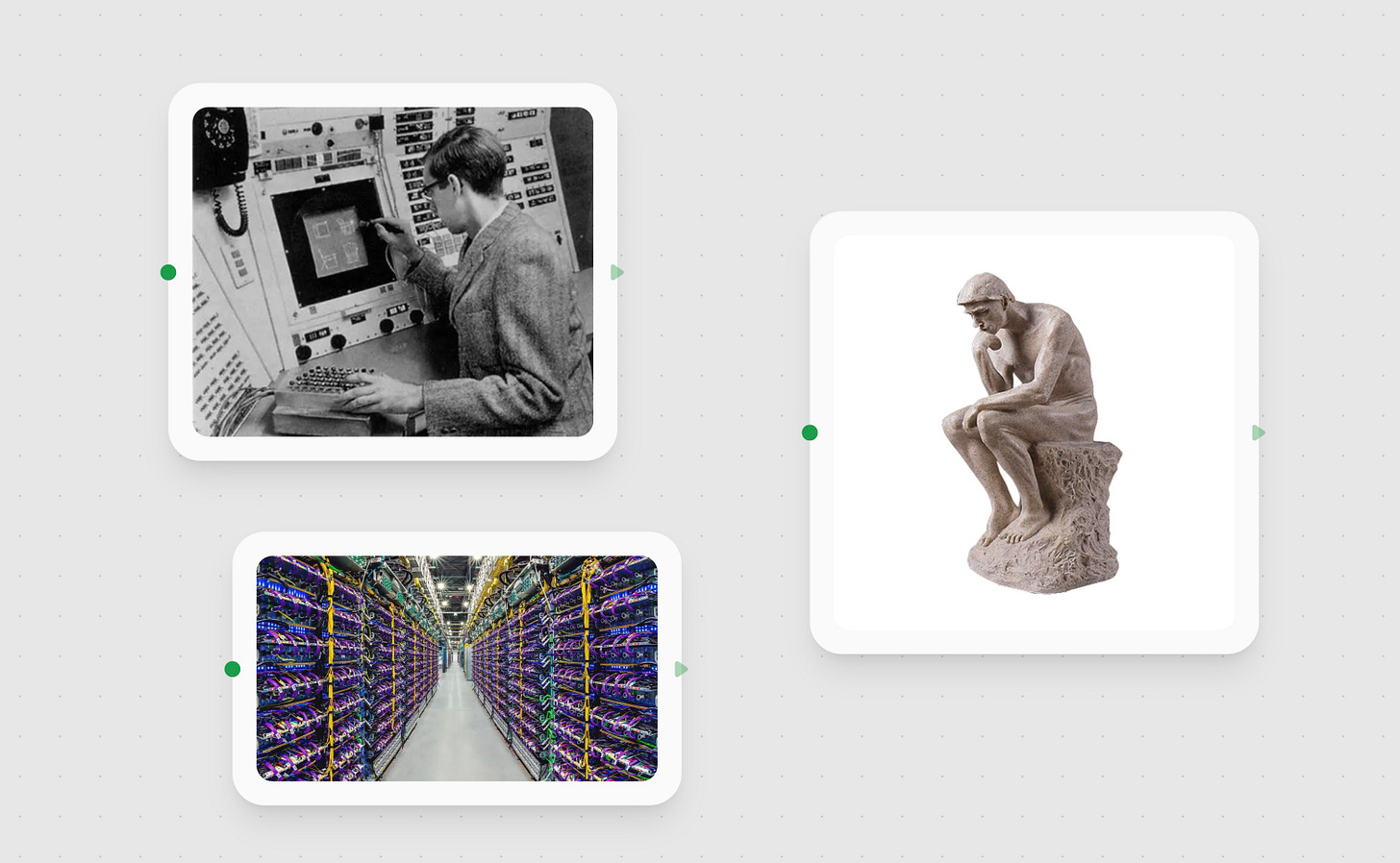

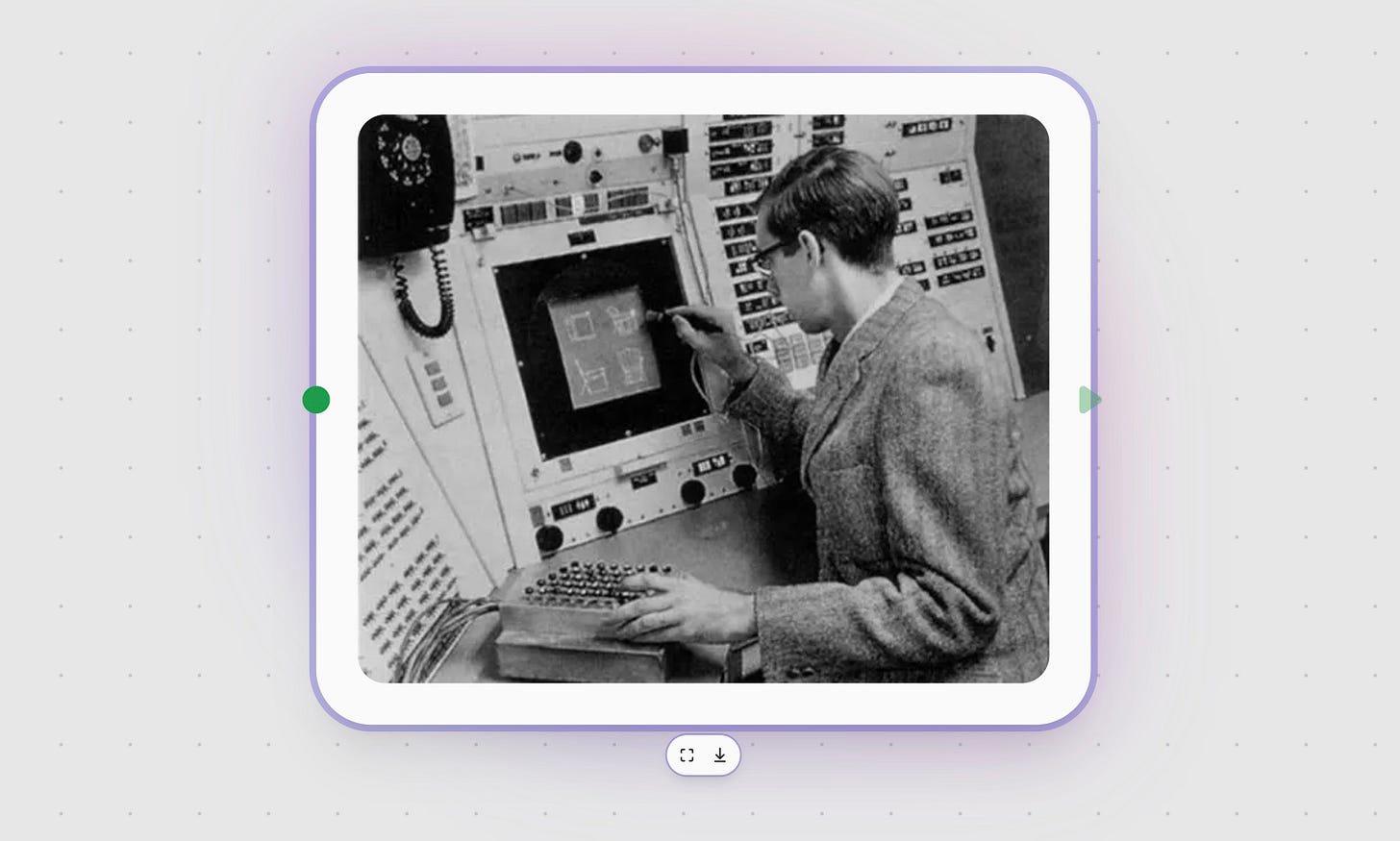

It’s 1963, and Ivan Sutherland is sitting before a glowing CRT at MIT, drawing directly on a computer screen with a light pen. His Sketchpad system—revolutionary for its direct manipulation interface—contains something prophetic: a node-based constraint system, boxes connected by relationships, a directed graph of computational dependencies rendered in phosphor light.

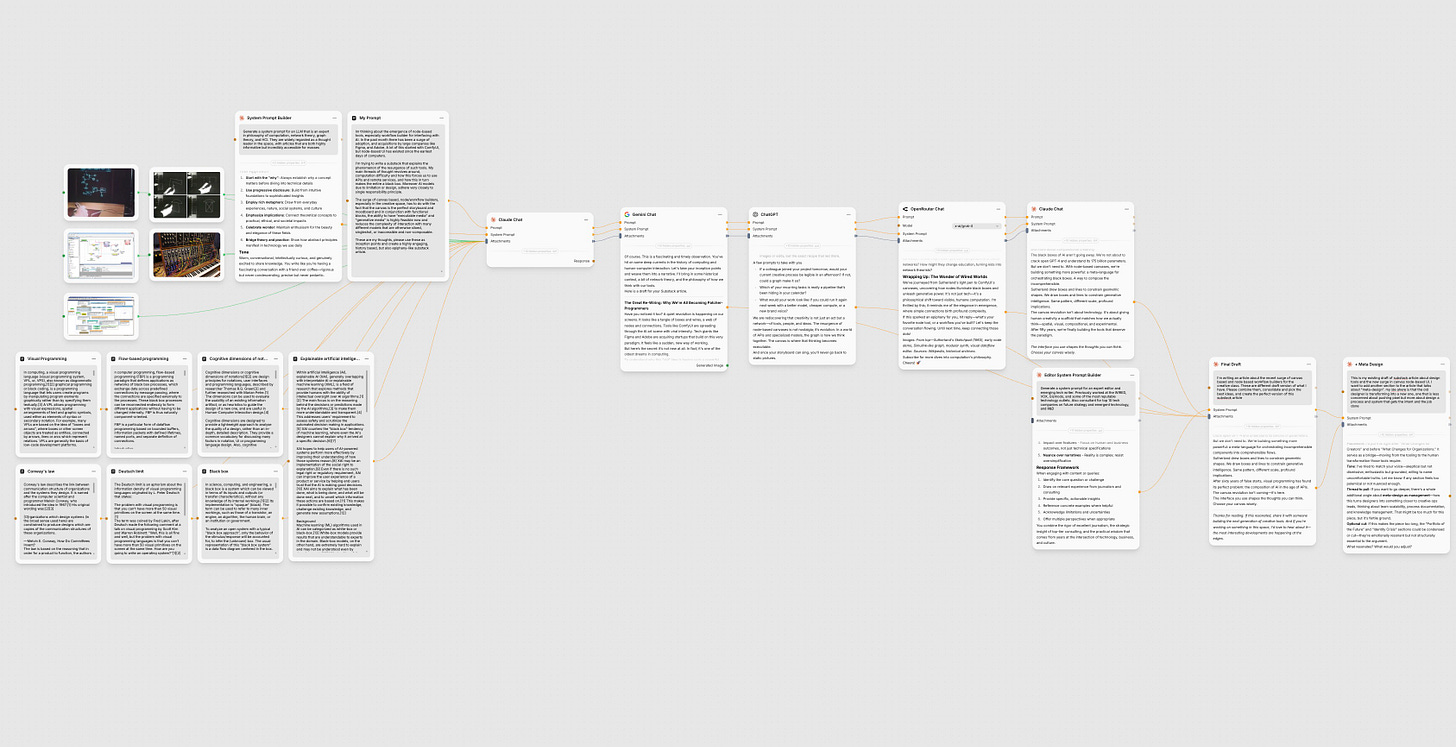

Sixty years later, a designer in Brooklyn drags nodes across an Adobe canvas, orchestrating AI models to generate images. In San Francisco, Figma executives sign acquisition papers worth hundreds of millions for a startup built on this same paradigm. ComfyUI workflows are viral on Reddit. Every major creative platform is racing to ship or acquire canvas-based workflow builders.

The same pattern, six decades apart. What took so long? Why now? And why with such intensity?

The answer is structural: AI has fundamentally changed the nature of creative work from operating monolithic applications to orchestrating networks of opaque, specialized services. Node-based canvases are the only sensible interface for this new paradigm of computation. What we’re witnessing is the emergence of a new medium that matches how we actually think about composition, makes invisible complexity visible, and transforms creative processes from private craft into shareable, executable knowledge.

The Great Unbundling

AI has shattered the monolithic application. For the last half-century, creative software was self-contained. Photoshop was a massive binary running locally. You could, in theory, understand the entire program. The computation was here, on your machine, legible if you cared enough to look.

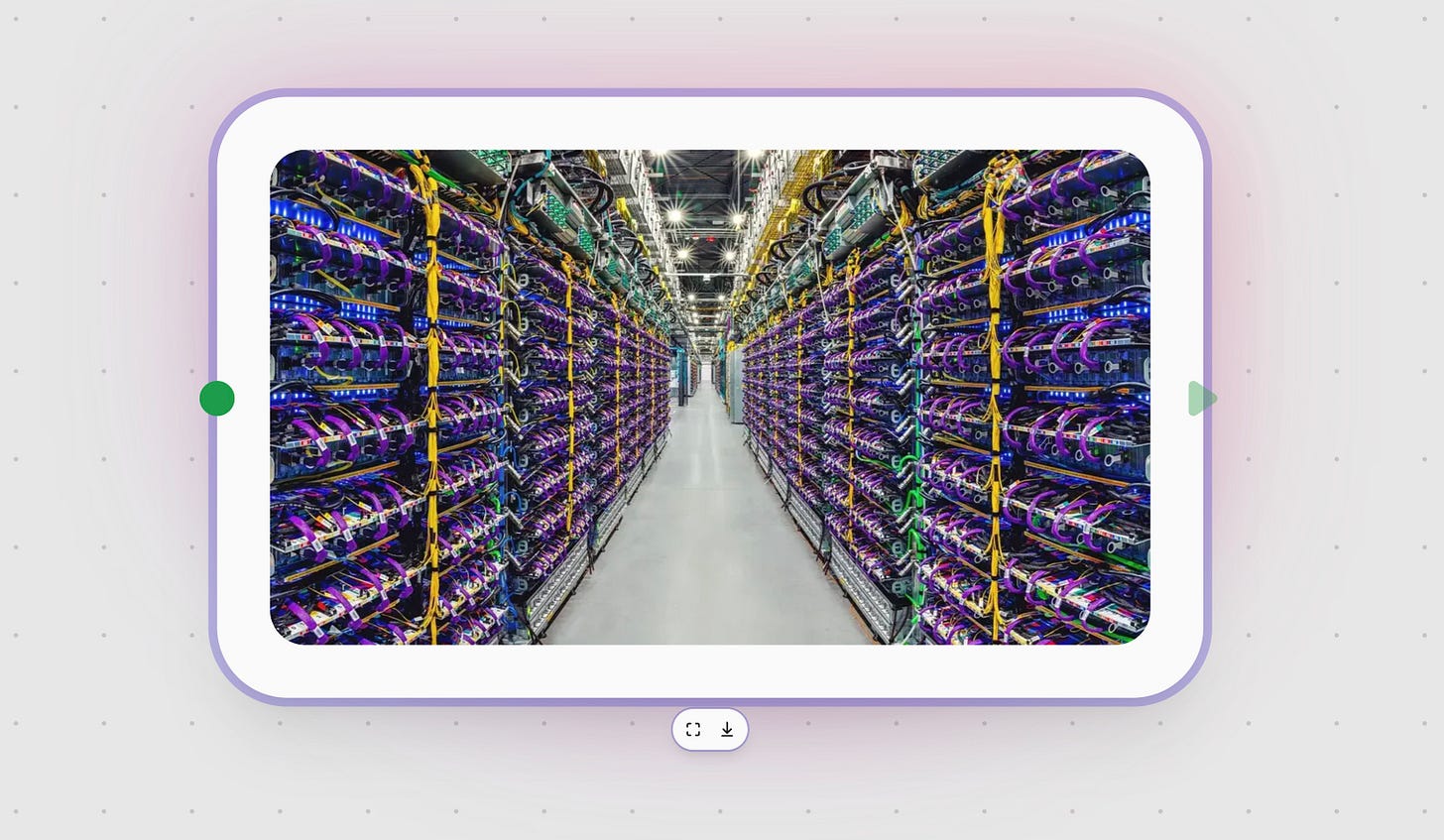

Modern AI has inverted this relationship to software. We now live in an API-first world where the really interesting computation happens elsewhere, on server farms, inside proprietary black boxes we can’t inspect. Each model is hyper-specialized: one generates images, another upscales videos, a third clones voices, a fourth gives legal advice. While we see modalities fused and abstracted at the application layer to give us the impression of multimodality, the reality is that most AI models are still mono or at best bimodal. As such, they’re still computational heavyweights that embody the single responsibility principle not by design but by practical necessity: training a model that does everything is exponentially harder than training focused specialists.

This creates two fundamental problems in comprehension and usability:

The Black Box Problem: These models are functionally opaque. We give them input, we get output, but the internal logic—billions of parameters trained on terabytes of data—is inscrutable. We’ve traded understanding for capability.

The Composition Problem: How do you orchestrate a symphony of single-purpose black boxes? Traditional software answered this with scripting—write some Python glue code to chain API calls. It works, but it’s abstract. The relationships between components hide inside the syntax of code.

This is where the node-based canvas returns as a solution to this new class of problems. Nostalgic, vengeful, and effective.

Making Thought Visible

The genius of node-based interfaces is that they externalize your mental model. Beyond convenient UI sugar, they’re a structural shift in how we represent computation. The canvas leverages what cognitive scientists call “external scaffolding”—offloading mental complexity into the physical (or in this case, visual) world. Instead of holding a 50-line Python script in your memory, you glance at the canvas and see the flow. Your visual cortex’s extraordinary pattern-recognition abilities do the heavy lifting.

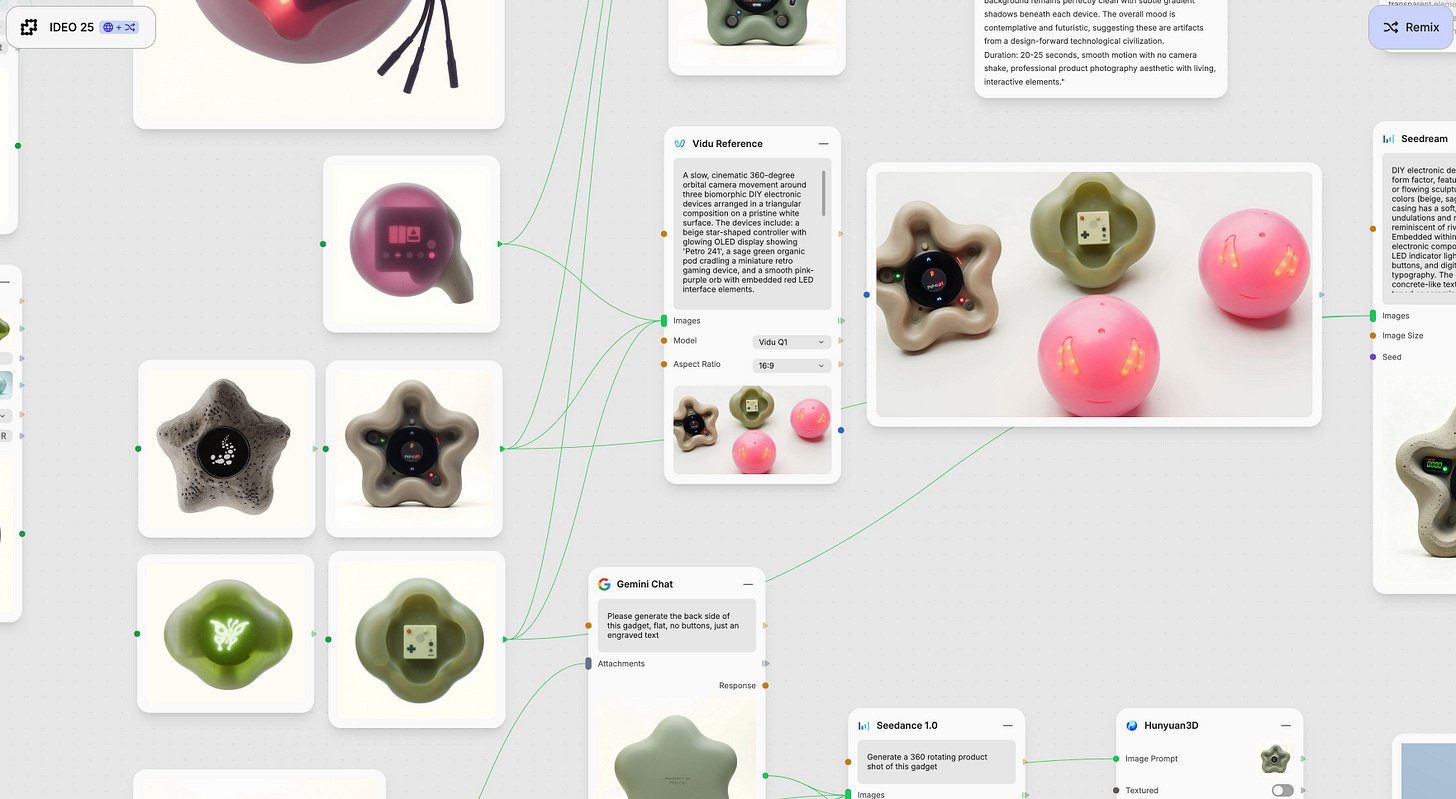

When you build an AI workflow, you’re not really writing a program in the traditional sense; you’re choreographing a data flow. Image goes in, gets transformed, gets upscaled, gets refined, video comes out. That’s not imperative programming (“do this, then do that”). It’s dataflow programming (“when X arrives here, transform it into Y and send it there”).

The canvas makes this tangible. Each node is a verb (Load, Generate, Upscale), and each wire is a noun (the image, the text, the video) flowing between them. The entire graph tells the story of your creative process, laid out spatially and legible at a glance.

In Human-Computer Interaction terms, this dramatically reduces cognitive load. It makes the abstract concrete. It transforms the invisible into the visible.

Conway’s Law, Visualized

There’s an old saying in software engineering called Conway’s Law: organizations design systems that mirror their own communication structures.

The modern AI landscape is radically distributed—models from OpenAI, Anthropic, Midjourney, ByteDance, open-source communities, individual researchers. We’re seeing a shift from monoliths to a decentralized ecosystem of specialized agents.

What better way to interface with that ecosystem than with a tool that is itself a visual network editor?

The node canvas becomes an honest map of the distributed reality we’re dealing with. It acknowledges that you’re not using One Big Application—you’re orchestrating a constellation of independent services. The tool mirrors the territory.

The Moodboard That Executes

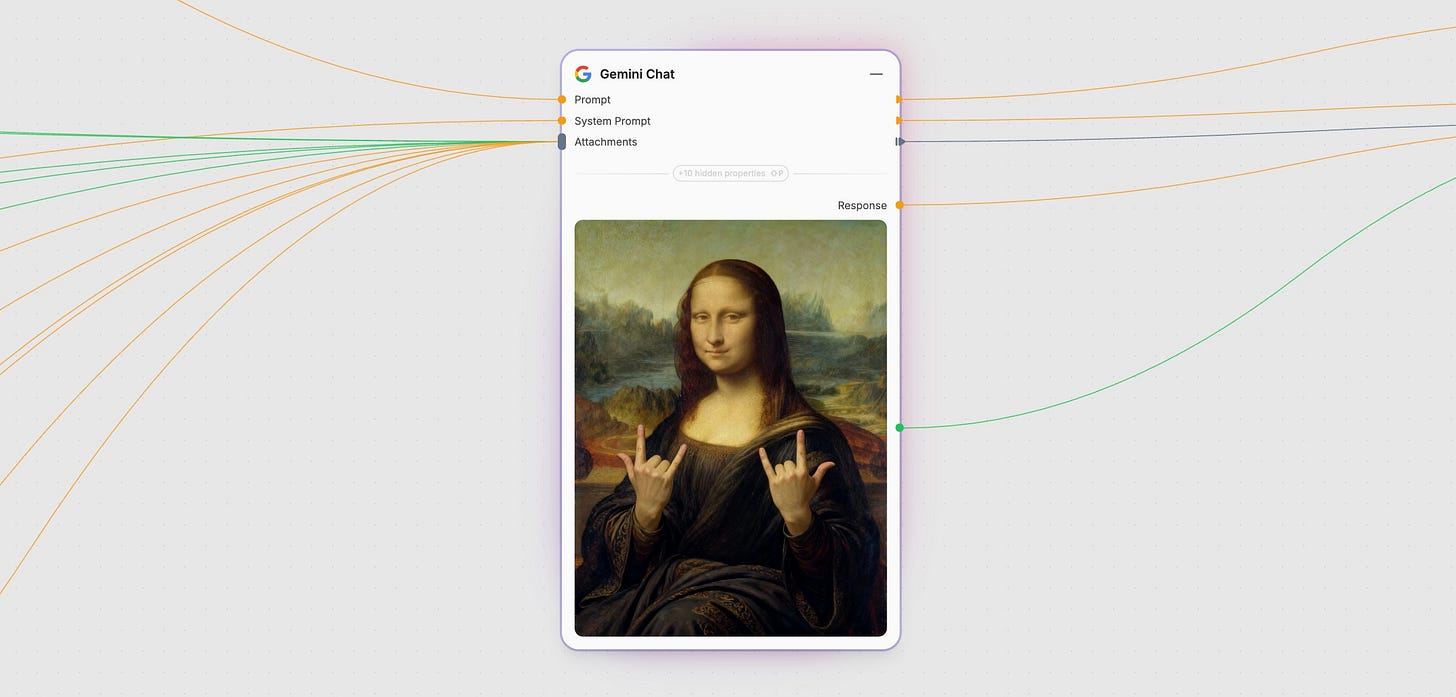

In the AI era, the canvas becomes executable media.

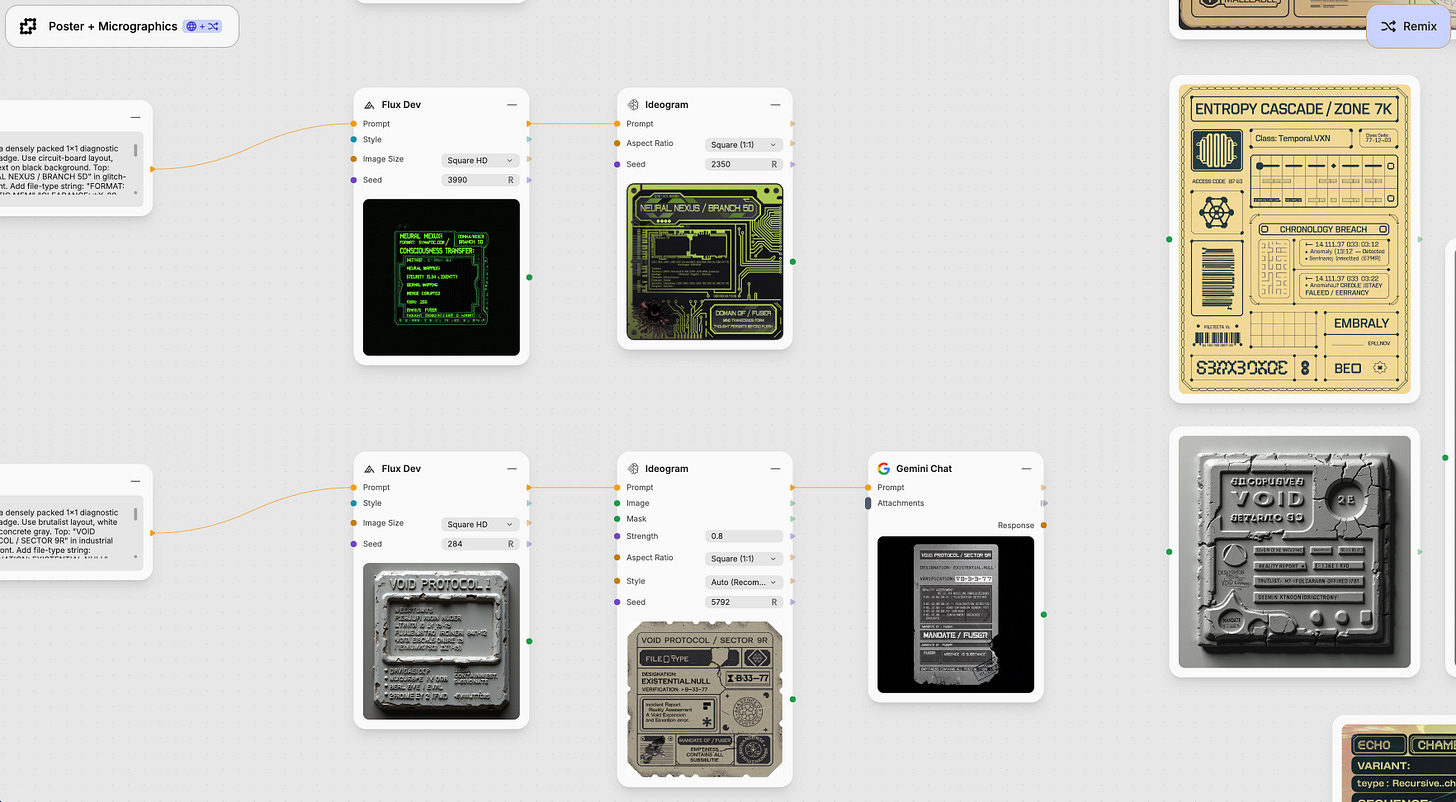

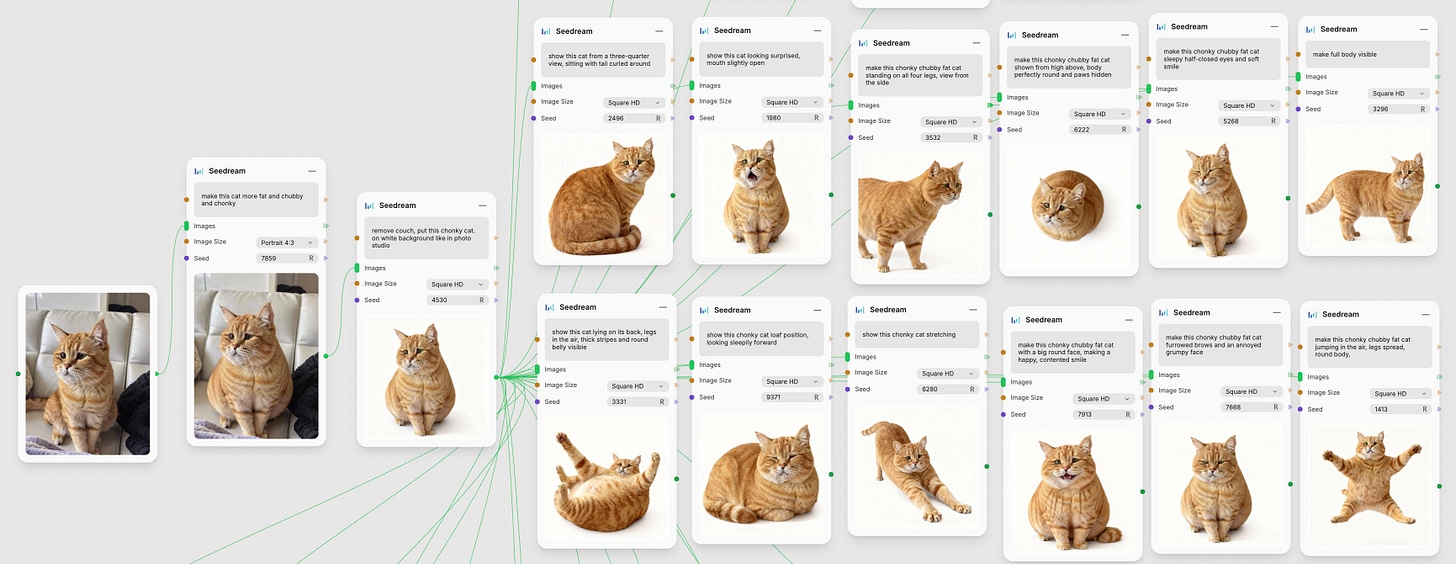

Traditional moodboards are static—pinned inspirations, reference images, color palettes. They communicate intent but don’t do anything. A Fuser canvas is different. It’s simultaneously a moodboard (showing your aesthetic direction), a storyboard (mapping your process), and a factory (executing the actual generation).

You’re arranging content, sure, but you’re also arranging processes. The artifact has less to do with the final output, and more with the workflow itself. You can share your canvas and someone else can see your result and run machine that made it, tweak its parameters, and generate a thousand variations.

This collapses the distance between inspiration and implementation. The plan and the factory become the same object.

Why Visual Programming Finally Works

Visual programming languages have a troubled history. Every decade, someone announces text is obsolete, that drag-and-drop blocks are the future. Every decade, they’re mostly wrong.

The criticism is real: the Deutsch Limit suggests you can’t have more than 50 visual primitives on screen without overwhelming users. Text is information-dense. Code is precise. Visual metaphors often confuse more than clarify.

But AI workflows are different:

1. Constrained vocabulary: You’re not doing general-purpose computation. You’re composing a pipeline of specialized operations: generators, transformers, upscalers, style transfers. Fifty primitives is plenty.

2. Inherent non-determinism: The same prompt rarely produces identical output twice. Traditional debugging (reproduce the bug, fix it, verify) is impossible. But visual experimentation is natural—move this node, reconnect that edge, adjust a parameter, see what emerges.

3. Maturity of infrastructure: Modern web tech (GPU-accelerated canvases, real-time collaboration, WebGL) makes these interfaces smooth. Fuser succeeds where predecessors failed partly because it’s not janky.

4. The right audience: There’s now a generation of creators who are computationally literate but not programmers. They understand logic and flow and composition, but they don’t want to write code. The canvas is already their native medium.

The Network Theory of Creativity

Creative work has always been compositional—building complex outputs from simpler, interconnected operations. A filmmaker doesn’t conceive a scene as a single atomic thought. You have to juggle cinematography, sound, color grading, pacing, and narrative simultaneously. The creative process naturally forms what network theorists call a directed acyclic graph (DAG): nodes are transformations, and edges are the flow of information.

We’ve always thought this way, but our tools haven’t always matched. We’ve used linear timelines in video editors, layered stacks in Photoshop, and hierarchical trees in file systems—each a partial fit for how we actually think about composition.

Node-based canvases nail it. They map directly to the graph structure of creative thought. They don’t just allow compositional thinking—they encourage it. They make dependencies explicit and experimentation cheap. Reconnecting a wire is easier than rewriting a script.

And when you combine this with AI’s modular, single-purpose architecture, you get a combinatorial explosion of possibilities. One image generator is useful. Ten generators, five upscalers, and three style transfer models create an infinite space of compositions.

The Philosophy Underneath

For most of computing’s history, programs have been texts—strings of symbols descended from formal logic and mathematics. The computer is a symbol manipulator, transforming syntax according to rules.

But humans aren’t primarily symbolic reasoners. We’re visual, spatial, embodied creatures. We navigate physical space, track objects in motion, recognize patterns in scenes. Our brains dedicate massive neural real estate to visual processing.

Node-based canvases reframe computation as spatial navigation. “Running a program” becomes “following a path.” “Debugging” becomes “observing flows.” “Architecture” becomes literally architectural—you can walk through it with your eyes.

This is a different epistemology of what computation is. Text says: computation is symbol manipulation. Canvases say: computation is routing information through space. Both are true, but they’re phenomenologically distinct ways of knowing, and the visual approach better matches human cognition.

What Changes for Creative Work

The shift from single prompts to full pipelines is a big deal. Final exports become snapshots. The real value is in the flow itself, which can regenerate outputs with new models, audiences, or constraints. Teams will build libraries of nodes and subgraphs the way they once built libraries of brushes, LUTs, and presets. And when you share a result, you can share the exact recipe, which changes how we teach, critique, and collaborate around generative work.

For organizations, this means reuse at scale. One graph can generate dozens of localized assets with full provenance and auditability. Compliance checks can be attached to specific nodes, embedding policy directly into the pipeline instead of PDFs. If a vendor’s API changes its pricing or degrades quality, you can see the blast radius across all your workflows and swap in an alternative. The graph becomes the shared source of truth. No more “what steps did you use again?” The canvas is documentation that never goes stale.

The Deeper Pattern

We’re rediscovering that complex systems are best understood and manipulated as networks.

Neural networks are graphs. Social networks are graphs. Supply chains are graphs. Biological systems are graphs. The internet is a graph. Your thinking is probably a graph—concepts connected by associations, not a linear sequence of propositions.

By building node-based tools, we’re acknowledging the fundamental structure of complexity itself, and in doing so, we’re making the invisible visible.

AI accelerated this realization because it forced the issue. When computation became opaque and distributed, when single-purpose models became the atoms of creativity, we needed a new language for composition. The graph was waiting.

Sutherland’s Prophecy

Ivan Sutherland titled his thesis “A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System.” He didn’t see it as a drawing program, but as a communication protocol between human spatial reasoning and machine logic.

Sixty years later, we’re continuing that vision at Fuser. The node-based canvas is a new form of technological literacy. It’s a blueprint for a generation that needs to orchestrate black boxes. A spatial language for composing with incomprehensible parts. It’s about making complexity legible, and letting us think with our eyes, not just with syntax.

Most importantly, it’s about democratization. When the interface matches human spatial cognition rather than machine symbols, more people can participate. The tool becomes less about programming literacy and more about compositional creativity.

We’re not about to crack open GPT and understand its billions of parameters. We don’t have to. We’re building something more powerful: a meta-language for orchestrating incomprehensible components into comprehensible flows.

Sutherland drew boxes and lines to constrain geometric shapes. We draw them to constrain generative intelligence. Same pattern, different scale, new implications.

After sixty years of false starts, visual programming has found its perfect problem: the composition of AI in the age of APIs.

The interface you use shapes the thoughts you can think. Choose your canvas wisely.

Thanks for reading. If this resonated, follow our work @fuserstudio, share it with someone building the next generation of creative tools or working with them. And if you’re working on something in this space, we’re hiring! The most interesting developments are happening at the edges.